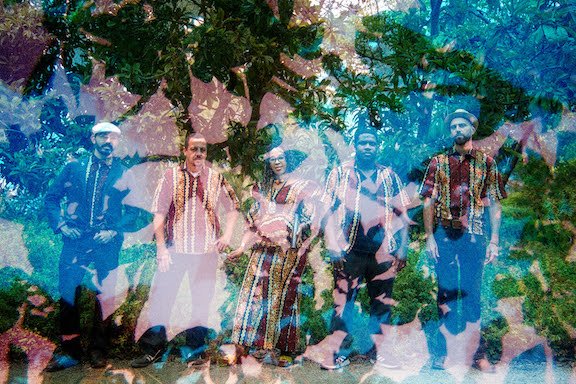

Orchestra Gold’s Mariam Diakite and Erich Huffaker

Photo credit: Ginger Fierstein

Oakland, California-based ensemble Orchestra Gold conjure a rare and artful fusion of African psychedelic rock deeply rooted in the Malian tradition. Emanating from a decade-long collaboration between Mariam Diakite of Mali and Erich Huffaker of Oakland, their music is a powerful intersection, transcending borders and boundaries to be a force of healing. Prior to the release of Medicine, Mariam and Erich (who translated for Miriam) joined The Eisenberg Review to discuss their new album, the building blocks of Malian music and more.

***

Medicine is the type of record that is very easy to get lost in… sonically warm and deeply rooted. And you can tell it comes from such an authentic place.

Medicine is a great title because music oftentimes is a balm that we reach for at times that we need it. Is that where the title comes from? Why is Medicine a befitting title for this group of songs?

Mariam says because it stems from her relationship with music, first of all. She likes to play music that feels healing to her and she knows that it's been medicine for her. And because she knows it's been medicine for her, she also knows that other people are going to feel that too.

I think that's a beautiful sentiment that carries through. You know, I'm taken to one of the first records that I ever heard. My mom was a big Todd Rundgren fan, and he has an a capella record that he did, entitled Healing, that she was playing in the hospital after I was born. So I think it speaks to a similar type of thing. That's very, very powerful.

Yeah, thank you.

The spirituality that I hear kind of pervading the record, and certainly the music making process ... I know the collaboration between the two of you extends for a decade. How did Orchestra Gold get its start? How did the two of you meet?

Mariam and I met in 2006 when I was living in Mali for an internship I did. We met through my djembe teacher, “Matche” Traore. At that time I was just studying the drumming and dancing music of Mali. And then Mariam and I became friends.

And it wasn't until probably eight or nine years later that we started working together on music. One day I brought my guitar with me to her compound, her family's compound, and we sat down and we played a song together for the first time, and it was just kind of magical. And so little by little from that point, we started collaborating on songs.

And then we were working on music together one time when I had gone to Mali, and we were in Ségou, and I posted the question, I was like, "Would you want to work on this in the US?" And she was like, "Yeah, let's do it." And so we started figuring out how to get her an artist visa to come here. It's been slowly but steadily building.

I think, like you pointed out, the interesting thing about this project is there's a lot of people doing fusion-y type things, but our fusion is very ... It's a very simple fusion because it's really rooted in the coming together of our experiences: her, that's now spent a lot of time in the United States, and me, who's spent a lot of time in Mali, and the meeting of those two worlds in this ongoing conversation between the two of us because we're always playing and creating new things together.

I hear that conversational aspect come through and certainly... I mean, all music is an active fusion at some point, right? You are synthesizing creative ideas irrespective of genre. You're synthesizing backgrounds.

You did mention there are a lot of other folks doing the fusion thing. I know you got to work with Chico Mann from Antibalas on the record.

Let's talk about and dive into what that process looked like a little bit. It's hard to imagine the recording process being anything, based on the sound of the record, anything other than everyone in a room tracking to tape. Is that the case?

The process was us kind of building the songs ... Everything kind of starts with Mariam and myself, and then those kind of go through this filtering process with the rest of the band. And sometimes that takes a while and sometimes it doesn't, and then we just kind of end up with the song.

With this particular record, yeah, we recorded those tracks to tape at the Tiny Telephone studios in Oakland.

Marcos was a really ... Chico Mann, he was a really, really ideal fit for this. He has another project: Here Lies Man. It's a beautiful three, four records that they've put out, and it's like, metal meets Afrobeat. And it's just really, really groovy and really awesome.

I think he operates in this space where he's blending things in that same way too. He got what we were trying to do and he added another dimension of psychedelia; just a really refined taste and feel for everything that was really awesome to work with him.

He came in at the end, he kind of did the mixing of it.

Beautiful. So we have him partially to thank for just the kind of warm, enveloping sound of the entire record.

Yeah.

I love the way that the record is mixed because it takes and so beautifully marinates all of the sonics.

Mariam, your raw, just mesmerizing vocals that just ... They sound so effortless. And certainly, Erich, your guitar playing, it helps kind of propel everything in the arrangement forward. That's so cool.

I know Here Lies Man because of the label, RidingEasy Records.

Oh, okay. Yeah. Yeah.

It's a different type of approach. They're very Black Sabbath. They love that classic stoner metal sound.

Yeah. Which is cool. I loved a lot of that stuff too, man. There's a couple of songs that we're working on for the next album that have a little bit more of that vibe in there too. So I'm excited.

I would love to know how she [Miriam] started singing. And I always love asking, and this is a question for both of you, first musical memories, because I often find those pretty instructive.

She learned how to sing at Madrasa in Mali.

Wow. What age?

Seven years.

When they would do their compositions, like the writing in Arabic, they would sing with it.

What a way to learn. And that I think speaks to kind of the deep rootedness that I hear, because you mentioning the djembe earlier, Erich, it reminds me of ... Are you familiar with, either of you, the percussionist Weedie Braimah?

Yeah. Yeah. He's a friend.

That's awesome.

Weedie sometimes pops in through Northeast Ohio every once in a while. And I got a similar feeling listening to Medicine as I did listening to The Hands of Time.

Oh wow.

Just in terms of ... Certainly the sounds of the Africa diaspora has moved far and wide, but I hear ... It sounds like a definite sonic progression towards something that's a little bit more futuristic.

I don't have a really good sense for the music of Mali or the musical heritage. How does that inform the music?

The way that we understand music is quite different in Mali, she says, than here.

Even the way we approach things like arranging music are very different from each other, from how folks do it here. There is a modern style that seems to be influencing things, but still, our approach to doing everything is very different.

And how is it different?

She said that the melodies are quite different. The structure of the songs is different, like the way we do choruses and then we'll oftentimes respond to the choruses in a way. And the way that we stop and start music is very different.

The challenge for me as a westerner studying Mali music is that everything follows a lead point person. And so a lot of times in Mali music that will be the singer.

So when I first started composing music for her, I didn't really think about her vocals or how ... I just assumed that she would be able to sing this part inside of this thing that I created without having had any input into it.

So I made all these complicated arrangements and I brought them to her, but she's like, "I can't sing to this. You didn't tailor it to my key. You didn't think about how ... " I mean, she didn't say that, but her vocals just were not going to fit. So I had to go back and work with her on the keys.

The vocals are the first thing. So you really have to follow the vocals. You have to take those into account when you're doing everything.

I mean, in the west, a lot of times, it seems like the vocals, you can create music and then add vocals in afterwards, but not in ... At least our collaboration, that's never really worked.

So that's why it has to be this collaborative thing. The vocals have to be a pretty important part.

There has to be a main groove where she can sink into a sense of comfort. And when she has that, she can really get comfortable singing on top of it. But that has to take into account her range and that has to take into account the right feel. And the music can't be too loud, otherwise she doesn't have the right dynamics.

So it's really taking into account the singing in a lot more detail than I ever had to do working with a Western singer.

So vocals first, as it should be. laughs

Yes. Vocals first, as it should be.

And that's so fascinating.

So it's almost as if ... Because certainly, if you had asked me just from the way that I typically approach listening, the groove is very, very important. Groove is what hooks me into the song. It's just what takes you in and gets you there. So it's almost as if the approach is the vocal is kind of what establishes the pocket for the groove and those two things then work in tandem to create the rest of the song.

There is instrumental music in Mali too, but I mean, if you just go to a wedding, you watch the singers and the drummers and the dancers, or maybe there's guitar and orchestra style, but it always starts with someone grabbing the microphone and starting a song. It always starts with someone singing a song and then everyone comes in after that to accompany it in some way, shape or form.

That's beautiful.

I'd be fascinated to know, between the both of you, what are Malian records of influence, either old, new, that are representative that I should look to as I'm just listening to understand the style a little bit more, maybe that would create a little bit more context around the sounds that you guys are creating?

Salif Keita.

... Would be a good place to start.

Yeah, Salif Keita or Ali Farka Touré.

Who just released a great new record with Khruangbin. It sounds terrific. That was a really cool record.

Yeah, happy for that.

Very happy for that too. They're wielding their influence in a very mindful way, I feel like, because it could very easily go a different direction…

It very easily could.

…especially at that level of success.

Yeah. I'm sure it's hard to make collaborations of that ilke work out in ways that I simply don't understand.

In what way?

I don't know. Finding common ground sometimes can be tricky.

But then again, sometimes chemistry works in unexpected ways too. So people just find each other and start having a conversation. And if you can have a good conversation with someone, you could probably collaborate musically with them.

Maybe I'm kind of going back on what I'm saying a little bit, but music is so magical and mysterious, you know? I think that it's important to have some respect.

But where I was coming from when I said that is just groups are successful. There's a lot of voices that have influence over what happens and what doesn't, you know?

I think that's true. And I think a lot of them, the more success you achieve, the more they come from outside the group or ensemble itself… people that aren't a part of the creative process that are attempting to dictate the way that process should go or what should be done with the end result of that process.

This part of the conversation, particularly the kind of question I'll ask as a coda or final question, is we were talking about Khruangbin, we were talking about ...

It seems like there's a renewed interest in sounds and grooves and music cultures from around the world, but there just hasn't been ... I mean, I feel like a lot of this has picked up in the past 10 years or so in the mainstream.

What do you two make of that?

Yeah, it's definitely happening.

I mean, as to why it's happening, there does seem to be a hunger now for new voices that are telling us new stories that we haven't heard about before because we've been so dominated by a culture where certain types of voices are really prioritized.

Now we could talk about the history of this country and stuff like that, but it's cool that there's an opportunity now.

Yeah, I think it's one of the more beautiful byproducts of probably this profound democratization we've experienced, not just in music making, but in terms of how that music's then disseminated and distributed.

Yeah, totally. Totally. Yeah.

And in some ways, I was thinking about this the other day, I probably have access to more music from the fifties and sixties than somebody living in the fifties and sixties did because of all of the archives that are available and radio stations and all this other stuff too.

So it's like, those people had to listen to something once or twice and learn it.

But there was so much less, to your point. You were experiencing a very small fraction of all the music being created at that time.

Right. Right.

It's crazy.

Yeah.

All that being said, Mariam, Eric, thank you so much for your time. Congrats on the new record. It's terrific.

Thank you so much for having us, man.